by Joseph Stoutzenberger

Creator: Sun_Shine | Credit: ©Sun_Shine/Shutterstock

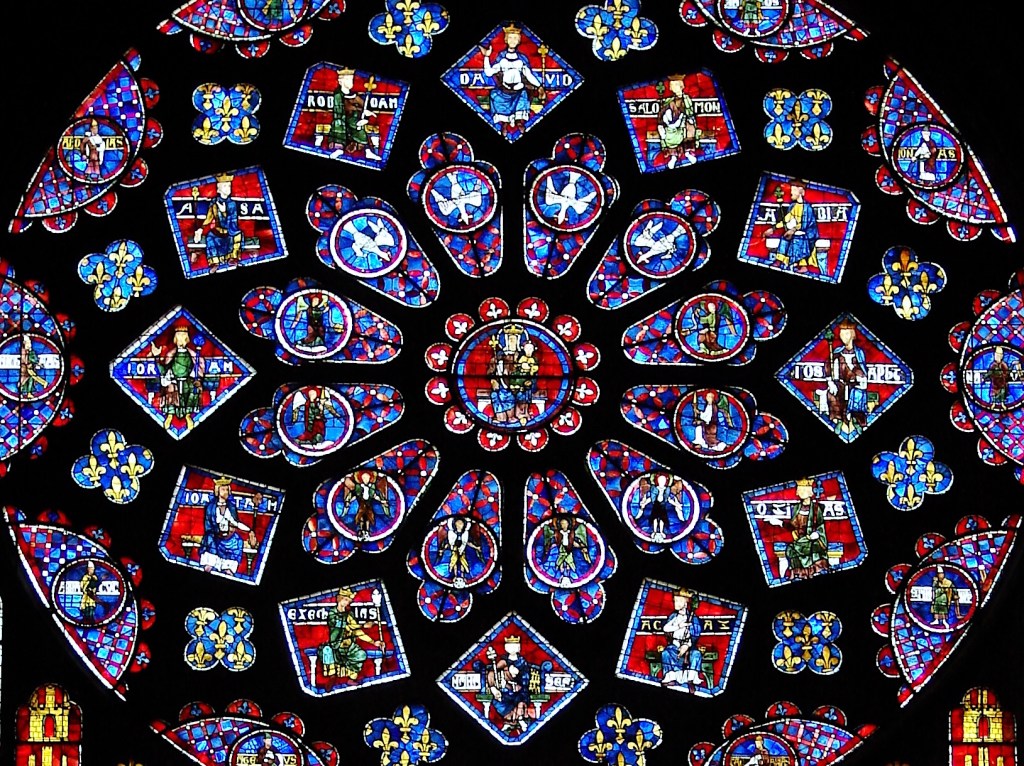

Some years ago, I traveled through Europe. I was awed by many sites that exuded a sense of the holy. Walking down the center aisle of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, I saw a plaque on the floor halfway to the sanctuary that read, “From here to the altar would fit St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York.” It was hard not to be overwhelmed by the imagination and effort that people of the past put into creating such a magnificent structure. Notre Dame Cathedral, before its tragic fire, dominated a beautiful section of Paris. Chartres was home to a cathedral where the light shining through the blue stained glass inspired those inside to raise their hearts and minds to God. There were also plenty of places not strictly religious that were teeming with life—the little cafes of Paris and the fountains of Rome, the pubs of Ireland and the beer gardens of Germany, and the view of the Alps traveling from Germany to Italy. An outsider such as myself could easily look upon all of these wonders as sacred manifestations of the holy. A particularly touching religious site for me was the little chapel of St. Francis in the grand Basilica in Assisi (Cover photo, featured image), erected in his honor.

published on 15 October 2018

I discovered, however, that the most moving and heart-wrenching place I visited was the remains of the concentration camp at Dachau. On the train into the city, a poster advertised the upcoming “Dachau Folk Festival.” Again, from my perspective as an outsider, I questioned how music, dancing, and celebrating could take place in a town associated with such a dark past. I was struck by Hannah Arendt’s writings about what she called “the banality of evil.” She wrote about Adolph Eichmann, who claimed to do nothing more than arrange train schedules. He was simply doing his job, making sure that trains transporting thousands of Jews to the concentration camps to be murdered did not interfere with the trains taking soldiers to the Russian front. It was difficult, if not impossible, not to be moved to tears walking through the camp. I found a small stone on the ground there that bore rust marks of barbed wire. Along with rosary beads supposedly blessed by the pope purchased at the Vatican gift shop, it was the only souvenir I brought home from my trip. The barbed wire markings were probably recent, but they served as a fitting reminder for me of the horrors that went on there.

The first book I ever wrote is Celebrating Sacraments, meant for high-school religion classes and still used in some schools. It reflects a broader understanding of the Catholic concept of “sacrament” than was dominant before sixty years ago when most people associated the term almost exclusively with the seven key rituals that serve as stepping stones in a Catholic’s growth in the faith, the Seven Sacraments. After Vatican Council II, as an investigation into these seven was taking place, theologians and religious educators started to talk about the universality of “sacrament.” If a sacrament is an “outward sign of God’s grace,” then surely the earth itself is sacramental, and all God’s creatures are holy manifestations of grace. The love of God comes through in love shared within families and among friends, even in casual encounters taken for granted. Aren’t such exchanges sacramental? They are visible, tangible expressions of the presence of God—God’s body language. The Seven Sacraments are best understood in relation to this broader understanding of sacraments.

I bring up sacramentality as fundamental to a Catholic worldview here because a place like Dachau tests the limits of the concept. Even before Vatican Council II, American Catholics were reminded in the Baltimore Catechism that “God is everywhere.” Was God present at Dachau when thousands of people were being slaughtered there? Is God present when bombs obliterate the towns of Ukraine and many of the people in them are thoughtlessly killed? How can we dare to say that there is a loving presence of God everywhere when a devastating earthquake kills so many people in eastern Turkey and Syria? And yet we seem to sense that holiness underlies tragedy. Along the road to the Dachau concentration camp are memorial shrines erected by various religions and nations, reminders that we are entering a holy place. When someone dies in a car crash, loved ones erect little shrines at the site to honor the memory of the victim. In such circumstances, we can yell and scream at God. There are even biblical psalms to help us do so. But do we want to dismiss the lives snuffed out in tragedies as less than holy? Rather than dismiss God, isn’t it better to plead with God to find sacredness in lives cut short and sufferings endured? Before the Latin word “Sacramentum” was used for the presence of God in our midst, the Greek churches referred to “mystery.” God’s presence is frustratingly hidden from us, a mystery. Horrible tragedies, especially ones perpetrated by human beings themselves, shock us to search ever deeper into discerning God’s presence and to dedicate ourselves to counter such distortions of the holy. We are meant to be stewards of life, which is the sacramental presence of God. Honoring the dead, especially those callously dismissed as so much junk, calls upon us to affirm life.