by Joseph Stoutzenberger

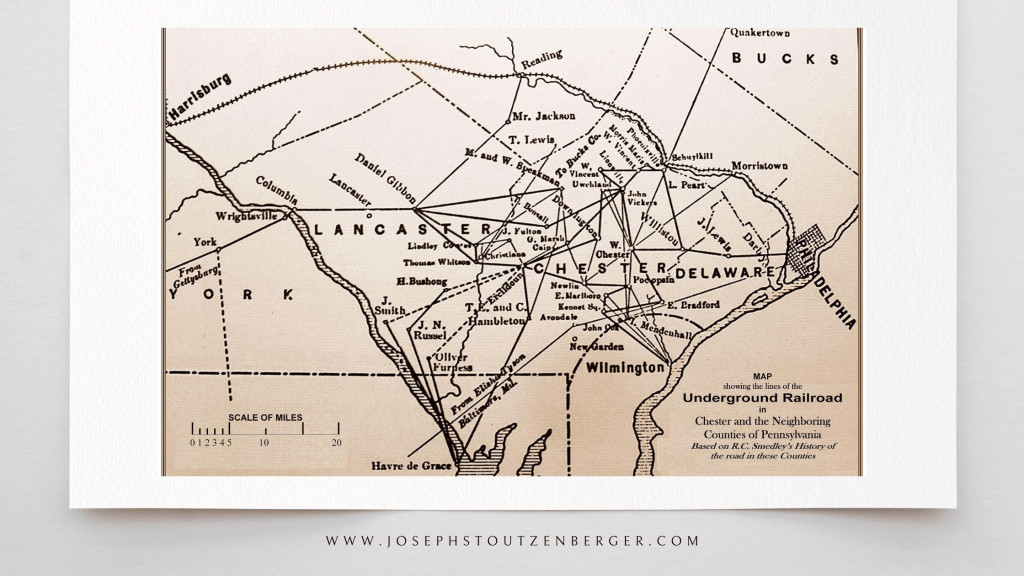

In the 1830s, a man who worked common jobs named William Otter kept a journal about his travels through the mid-Atlantic states. He spent some time in my hometown, Columbia, PA, on the banks of the Susquehanna, founded by a Quaker family to ferry people across the river. Columbia is not too far from the Maryland border. The Quaker Wright family harbored runaway slaves, and their home served as a stop on the Underground Railroad. A Maryland plantation owner, quite possibly a Catholic, as were so many plantation owners in Maryland, asked Otter to search for a slave who had run away. Otter joined with a Columbia sheriff, John Stoutzenberger, to kidnap the slave who was working for Wright at the time. Stoutzenberger devised a plot to get the runaway down to the river, where he and Otter apprehended him and had him returned to the Maryland plantation owner.

No doubt, that sheriff was an ancestor of mine; I believe all Stoutzenbergers in Columbia are related. I had hoped that I had relatives who were abolitionists, but this one followed the law of the time and apprehended fugitive slaves. In his travelogue, Otter mentions that Columbia needed no description as it had gained notoriety because it was the site of one of the worst attacks by whites against blacks in the antebellum north.

Such is the history of my hometown and my family in regard to race relations and racial attitudes. Columbia was a stop on the underground railroad. For a time, it was home to Stephen Smith, the richest black man in America prior to the Civil War. It was also a place of deep animosity among some white people against black people. In my youth, Columbia was still very segregated. The town was mostly white, but there were two stretches of poorer neighborhoods where black people lived. We played on the same little league teams, and as far as I can tell, relations were cordial. I have no idea if any black families attempted to move even a block away into a white neighborhood and if that would have sparked backlash from white people again. As late as 1968, the local KKK held a cross-burning in the playground across from my home to warn Columbia black people to stay in their place.

I attended an all-white Catholic grade school. A few months into seventh grade, Sister Gertrude told us that a new student was joining our class and that we were to welcome him and treat him with respect. The new student was a black boy named Willie. Toward the end of that year, a classmate handed out invitations to his birthday party at his house. I was looking at it over lunch with other students. Willie asked me what it was. I told him it was an invitation to Scott’s birthday party and that everyone in the class was invited. Willie said he didn’t get one. I said, “Oh, everyone is invited.” That Saturday at the party, everyone seemed to be there. I sat by the door when Willie showed up, dressed in a vest and a bowtie and holding a present. Scott’s grandmother opened the door and asked Willie what he wanted. He said he was here for the party. The grandmother turned to the mother and asked her, “Did you invite this colored boy?” The mother said, No. The grandmother turned to Willie and said, “I’m sorry. You weren’t invited. We are having dancing, and there are no colored girls for you to dance with.” My heart sank as she closed the door to Willie. I felt so guilty. Of course, blacks and whites can’t dance together; how stupid of me not to realize that. Why was I so foolish as to put Willie in this horrible, humiliating position. It was all my fault.

I tell those stories because they illustrate what Jim Wallis calls America’s “Original Sin.” By no means is deep-seated racism ancient history, and certainly, American Catholicism has been right in the thick of it. As many observers have noted, Sunday is the most segregated day of the week. Most Catholic churches in the Archdiocese of Philadelphia are made up almost entirely of white people. Some city parishes remain vibrant because of an influx of immigrants—Hispanics, Vietnamese, and Africans, and some have a smattering of black parishioners. A rare few are predominantly black. Most Catholic schools at all levels remain predominantly white. Independent Catholic grade schools now offer free or low-tuition education for poor, predominantly black students, and some city schools have become more integrated. There are some black clergy and even bishops in the U.S. Interestingly, six African Americans are in the process of being named Catholic saints. On a personal level, I now have a number of mixed-race, black and white, members of my extended family, and, unlike when I was a child, I presume they dance together on occasion. But is the Catholic Church today noted for an anti-racist agenda?

When I moved from my small town to Philadelphia with its strong Catholic population, my impression was that Catholics placed an emphasis on “being nice.” They tend to be kind and cordial. A question is, given the lingering effects of racism in the country, is that enough? Given the depth and scope of the problem, combatting racism entails being more than nice. It requires making a priority to address the racial divide in the church and the country and dedicating resources to counteracting all forms of racism. That man, who was kidnapped in my hometown and sent back to slavery, and my classmate Willie deserve nothing less.