by Joseph Stoutzenberger

Many years ago, my brother Rich went off to a summer graduate program at Boston College. A few months later, he stopped off in Philly to see me with a woman he had met there. We chatted for a while, and then I suggested we go out to get something to eat. I told them that there was a Chinese and an Italian restaurant nearby. The two of them looked at each other; and the woman, Sharon, said, “We don’t like Chinese food.” I was taken aback. The simple, magical word “we” hit me like a lightning bolt. Here was my brother, whom I had shared a bed with growing up, with a woman I had never met, and after a few short months they were saying “we.” Some people never get to the point of experiencing “we” with one other person, let alone with friends or a community. What a blessing it is. Rich and Sharon married and continue to be “we” over forty years later.

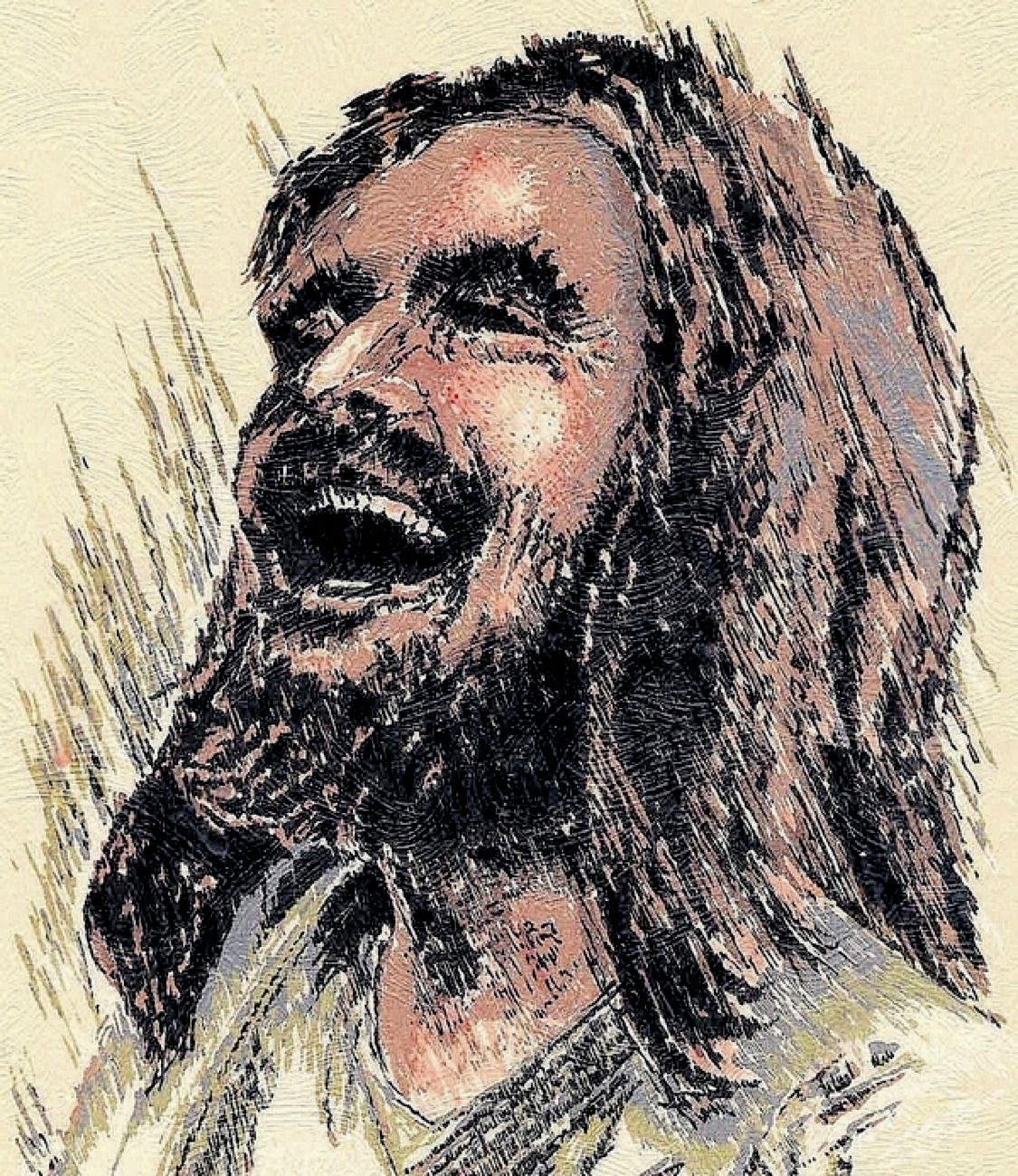

It reminds me of the story of a saint we heard about in grade school, St. Damien of Molokai. He was a Belgian priest sent as a missionary to Hawaii. He took up residence on the island of Molokai, where people who had contracted leprosy, Hansen’s disease, were sent to fend for themselves. Damien established structures to make life more pleasant for these people, and saw to it that they were treated with respect and even buried with dignity. He, of course, celebrated Mass with the sick; and during one Sunday service he began his sermon with the words: “We lepers.” He had contracted the disease himself and was no longer an outsider helping them but was one of them. He had become a “we” with these people who were cast aside by the powers on the main island who went to great lengths to keep their distance. Damien is recognized as a saint because he lived the Christian message, entering into the joys and suffering of others, and paid a price for it. His experience mirrors what Christians believe about Jesus, that, despite his divinity, he became one of us, even unto death.

The Christian God is trinitarian in nature—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. In other words, the Christian God is a “we.” In Jesus, God is not separate from human beings but one of us. That divine presence remains in our midst even today as the Holy Spirit. Despite Jesus’s best efforts, it is hard for us to grasp this intimate connection we have with God. The second half of the Gospel according to John has Jesus very powerfully telling his friends that they are one with God and with one another. “You will know that I am one with the Father. You will know that you are one with me, and I am one with you,” and then, “I have told you these things while I am still with you. But the Holy Spirit will come and help you, because the Father will send the Spirit to take my place” (John 11: 20,25-26). Jesus is exhorting them to recognize the cosmic “we” that he is intimately in touch with in his connection to the Father and that is still present among us.

A discussion of the magic of experiencing we-ness must recognize that nearly half of American adults are not married, and that even being married is no guarantee of such an experience. To attain a sense of “we” with another is a great gift, a blessing from God and the work of human hands. It may or may not happen in a person’s life, married or not, but it is what we are designed to be. It is, in a sense, an art—the art of loving. Even fleeting moments of we-ness are holy. “We” can be a group of women who support one another and regularly gather for sharing stores; or older men who walk together and talk sports every Sunday, occasionally opening up about more personal matters. “We” is ultimately a profound longing we all have. St. Augustine tells us that “Our hearts are restless until they rest in you.” We don’t exist merely as isolated objects; rather, we are always in relationship, and God is present whenever we open our heart to another. In the words of philosopher Martin Buber, we are inherently not I-It but I-Thou. We can try to live otherwise, building physical and emotional walls as best we can, but we never succeed. That stranger across a crowded room always calls us, as the musical “South Pacific” reminds us.

We may not venture out into an unknown place, like my brother’s summer journey up north to Boston College, and come out of it with a breakthrough experience into we-ness. The Christian message is that all people are “we,” and the Christian vocation is to expand our realization of we-ness beyond those we are comfortable with. “We” is magic, but it is God’s work, the work of the Spirit, who works through us. Every encounter with another is an opportunity to experience that magic. To paraphrase a traditional Catholic hymn: Come, Holy Spirit, make our hearts ready to step outside of ourselves, to give and receive, to know the magic of “we.”